Building a search engine for the ASX

This post-mortem details the technical architecture and product evolution of an unstructured data search engine I built for the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX).

Problem Discovery

The inspiration for this project came from a friend telling me of a stock that he claimed was a prime takeover target. Like many “sure things” I’ve come across I proceeded to check the latest announcements, financials and other associated information. The company itself seemed somewhat mediocre, one specific filing stood out: they had recently initiated a “Strategic Review.”

I wanted to cross-check this trigger against their history, but there was a complete lack of tools to perform granular text searches across historical filings and across companies. It occurred to me that I couldn’t do this for the entire exchange either. If I could aggregate mentions of “strategic reviews” or “asset divestments” across the ASX, I could identify sector-wide trends and health signals that are usually buried in unstructured PDF text.

After all if I could know the aggregate of strategic reviews and their outcomes would that not tell me something even just a part of the puzzle about the current state of a company, a sector and the health of the ASX at large.

Exploration

Years prior to this I had been doing an ETL project for a professor to extract information from complex drug trials to build a regression model for understanding whether or not a drug had likelihood in succeeding or not. From that experience I remember vividly that

- Parsing PDF’s is truly nightmarish

- There is an absolutely incredible wealth of data locked away in them if you can get it out

Anyone who has built a parser for PDF’s understands the pain of endless edge cases one must navigate when parsing text or information from them.

To map out the problem space for the ASX, I sampled 50 announcements across various categories. The variation was striking from standardized digital text, high-resolution infographics, to low-quality rasterized scans.

The Extraction Pipeline

I implemented a hybrid extraction strategy to handle these varied formats. For digital text layers, I used PyMuPDF due to its high-performance C backend. For scanned documents, I implemented an OCR fallback using Tesseract (here is a simplified version below).

import fitz # PyMuPDF

import pytesseract

from PIL import Image

import io

def extract_text(pdf_path):

doc = fitz.open(pdf_path)

text = ""

for page in doc:

# Attempt high-fidelity digital extraction

page_text = page.get_text()

# Fallback to OCR for rasterized/scanned content

if not page_text.strip():

pix = page.get_pixmap()

img = Image.open(io.BytesIO(pix.tobytes()))

page_text = pytesseract.image_to_string(img)

text += page_text

return text

This strategy worked well for the most part however there was an around a ~5% error rate. Some documents would parse with excessive spacing, resulting in text like T a x P a i d . . . . . 5 0 0 or L i a b i l i t i e s.

The Search Architecture

The next hurdle was Information Retrieval (IR). While a linear search (grep) is trivial for a single 100-page document, it is computationally infeasible for a low-latency UI scanning a corpus of 200,000+ files. To achieve sub-second results, I needed a proper inverted index.

I evaluated several backends:

- ElasticSearch: Industry standard, but the operational overhead and JVM memory footprint were excessive for an MVP.

- PostgreSQL (FTS): Attractive for its relational consistency, but I wanted more control over typo-tolerance and ranking out of the box.

- Meilisearch: I ultimately chose Meilisearch for its optimized prefix-search and ease of deployment.

Meilisearch worked great out of the box but hit a scaling bottleneck when it came to large documents (annual reports) which created significant indexing lag and bloated the search results. Returning a 200-page document for a single keyword match is a poor user experience after all.

To solve this, I implemented a semantic chunking strategy. By breaking documents into overlapping text segments linked to a master Document ID, I could return the specific page or paragraph relevant to the user, significantly increasing the “signal” in the search results.

Overcoming Character Positioning Artifacts

The aforementioned error rate really shone through here and presented an interesting engineering challenge. Some PDFs store character coordinates rather than logical strings, resulting in the parsed text like T a x P a i d . . . 5 0 0.

Since this breaks a token-based inverted index, I had to decide between a heavy dictionary-based re-stitching heuristic or moving forward with the 95% of documents that parsed correctly. I opted for the latter to maintain ETL velocity for the beta, but it highlighted the inherent fragility of PDF-based data pipelines.

There was a great temptation (and many attempts) to solve this problem but after several fruitless hours I began to realize how this won’t be the blocker that answers whether the market fundamentally wants this product or not.

Architecture & Infrastructure

To keep costs low I decoupled the heavy lifting from the user-facing application.

The core ETL pipeline ran on a dedicated local worker node: an old T440P Thinkpad with 16GB of RAM. This machine handled the CPU-intensive tasks: polling the ASX feeds, normalizing text, and enriching metadata. This allowed me to keep the cloud infrastructure lean.

While there was some consideration of whether I should have more redundancy built in say if my power went out, internet turned off or someone simply closed the lid for the purposes of keeping this a rough and ready MVP I figured I could get away with it.

The frontend was a Next.js application deployed on Vercel, communicating with a Meilisearch instance on a DigitalOcean VPS.

Launch and Query Optimization

The beta launch had autocomplete, 1 year of data and a few companies with a full announcement history indexed, and some minimal filtering functionality. I started on a 4GB Digital Ocean VPS at first but I moved off that after trialing with a few users and finding the search slow and dangerously maxing out the CPU usage on queries.

The Meilisearch instance was initially deployed on a 4GB RAM VPS but it was fairly evident it wouldn’t be able to cope with the writes from indexing new announcements every 5 minutes or so and autocomplete just hammering the server.

I identified query amplification as the primary culprit. With autocomplete enabled, every keystroke triggered a new search request. While it provided a slick UI I wasn’t really convinced it was providing much value while it was taxing the CPU unnecessarily.

After a few user interviews the main responses were some variations of “its cool but doesn’t help much for finding things” so I remained unconvinced of its value.

After all the experience should be more about delivering high-quality, relevant results rather than having a rapidly changing list of menu items available on every keystroke.

I disabled autocomplete. This immediately stabilized the CPU load and allowed me to focus on the quality of the primary search results.

I eventually upscaled to an 8GB VPS to give the inverted index more breathing room in memory, ensuring that even concurrent complex queries remained performant.

Approximating the Pain Point

Many engineers who have built exactly the tool they wanted know the satisfaction of designing for their own needs. But if you’ve taken the next step and tried to monetize it, you know the subsequent pain of finding out that your “itch” was yours alone.

There was an initial magic to pulling up every “Strategic Review” as I had imagined.

But as the French exclaim: Pourquoi? For what? While I had the text and a view of who was conducting reviews, I still had a massive amount of manual research left to do. The search was the start of the thread, not the end of the needle.

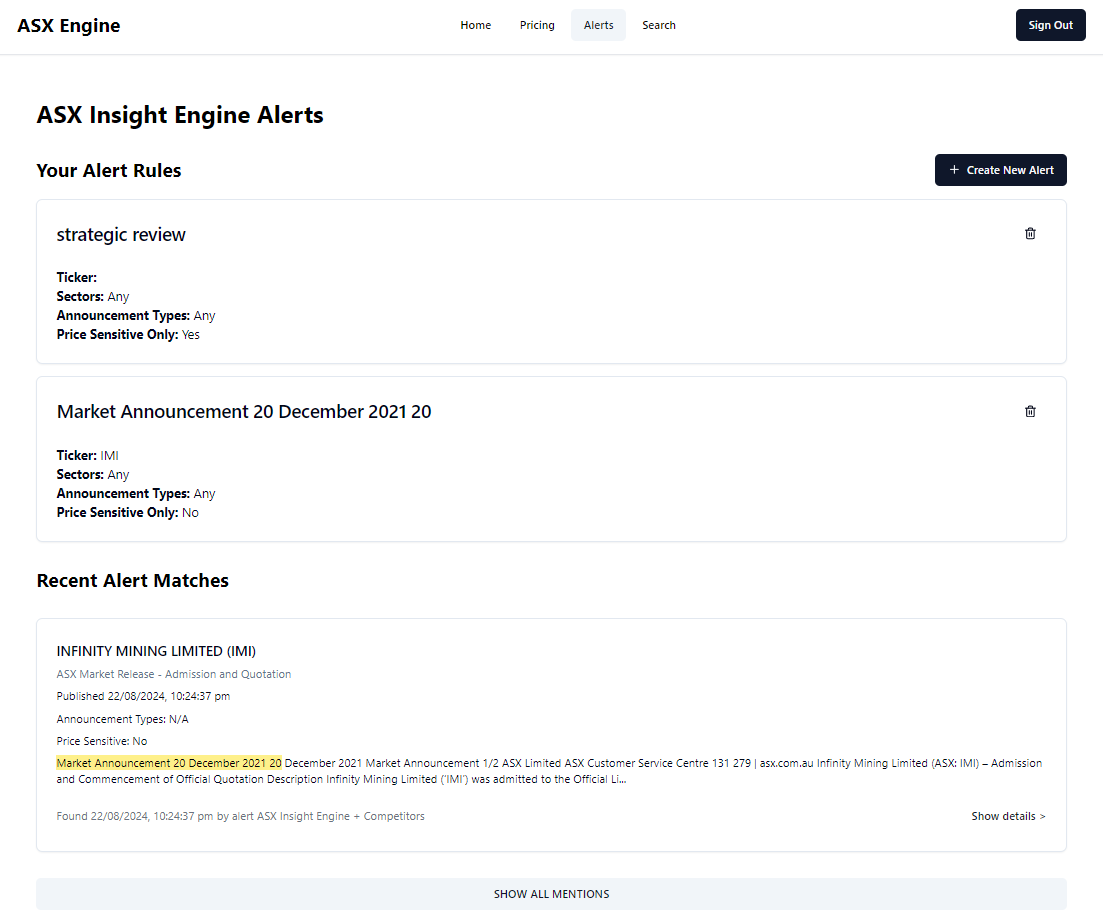

The Alerting Engine

Unsatisfied, I scoped out an alerting system. This was a minimal technical addition: during the parsing stage on the Thinkpad, I added a check to see if an announcement matched specific keywords.

To keep this efficient, I avoided a naive scan where every document is checked against every search term for every user. Instead, I maintained an inverted index of active alert terms. During the ingestion pipeline, a document is tokenized and checked once against this global list of “wanted” terms. If a hit is found, the system retrieves the associated User IDs and dispatches a notification.

I capped the free tier at two alerts and introduced a $10/month paid tier to see if anyone would bite.

The PMF Reality Check

The launch had gone well but I still was unsure what users were finding most valuable. I decided to paywall features and introduce usage limits.

After putting up the paywalls, usage didn’t really change. Most users would type a handful of queries, think “cool,” and then move on. Browsing through announcements simply wasn’t their daily workflow.

A handful of paying users emerged. Lawyers, IB analysts, and dedicated researchers but there was no real consistency in what they wanted. Some bought for the alerting; others just needed to find one specific historical document. Most people I talked to only needed to perform this kind of deep research once every few months. This was the first sign that:

- I didn’t have Product-Market Fit (PMF), but I was in the proximity of a problem.

- The problem was disparate. A generalized solution didn’t provide enough frequent value to justify a broad subscription model.

Herein lies the issue: I built a product to solve a problem I thought I had. In reality, I had a curiosity. I didn’t want “deep” information, I wanted shallow context around signals.

Lessons and next steps

I tried a few more “engineer-brain” features. I pushed the filtering to the extreme, allowing granular searches like “Show me every African Gold miner with a market cap between $30M and $50M mentioning ‘Tariffs’ that has had recent price volatility.”

I also built in price reactions so you could see exactly how much an announcement moved the market in real-time. But again, these launches saw small upticks in usage followed by stagnation. The engine was powerful and there were many interesting threads to pull on however there was no workflow capture.

And so like all classic products that gain traction but stagnated after a handful of paying users I decided to do what everyone tells you to do in the beginning and conduct some thorough customer research and find what end users actual workflows, pain points and existing solutions are.

I interviewed hedge fund managers and IR professionals. They all said the same thing: they use Bloomberg or CapIQ for the initial filter, but they always default to the source PDF. Why? Because companies bury the “truth” in the fine print or use accounting sleight-of-hand that only a fine-tooth comb can catch.

An interesting insight after the customer interviews was very few even relied on Bloomberg or Cap IQ as the data was often out of date or just plain wrong. Despite the solution costing some 50k a year unless you were dealing with major US companies often you had to dive into the annual reports yourself.

The value add was not in replacing this workflow because the need for it to be completely accurate and the ability to look up the information was never really an issue as you were essentially looking for a handful of announcement types.

The real issue lay in either idea generation which was where the “sifting” was before committing to a deep dive. The deep dive is very laborious so you obviously don’t want to do it for every company given how much information can be hidden in fine print or other weird areas of a document or just calling up investor relations and interrogating them.

Where that leaves the project

Ultimately, I ran out of time and money. While the search engine for the ASX didn’t set the world on fire, many parts of it are serving as the foundation for my next project. And as always with projects like this you do learn quite a lot.

I recently experimented with an MCP server that gives LLMs access to this search engine and price/vol data which involves some interesting technical trade-offs regarding context windows and data density that I’ll save for a separate post.

If you’d like to follow along, I’ll be writing about the core technical learnings of my new project here (probably), or you can find me on Twitter or LinkedIn.

If you enjoyed this or have ideas for the space, reach out. I’m currently open to contracting roles. And if you’re one of the few who thinks the world does need this search engine, definitely DM me I’ve already done the hard part.